This is part of a series of posts following a gathering in Montreal, in which a diverse group of 15 people spent four days exploring different facets of thrivability.

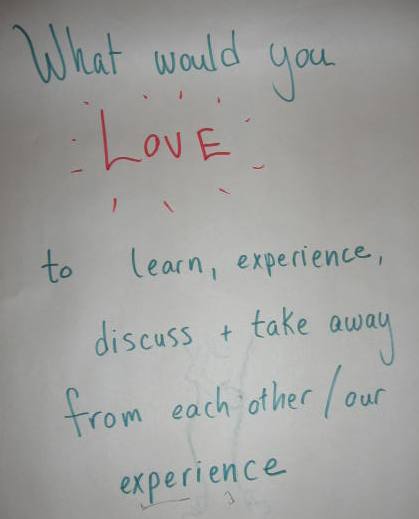

Throughout the Camp, we were almost obsessive about learning. It was extreme. We set learning goals on the first morning, and then reviewed our progress at the end of each morning and afternoon. We scribbled on countless flip chart pages and Post-it notes to document our learning. We did all this in a variety of light, playful ways. One afternoon, for example, we gathered in a circle and threw the equivalent of a ball around to each other; as each person caught the ball, he or she named something we had done and learned during that day. (We surprised ourselves with the number of things we had learned!) We also approached our learning from a host of angles. Several times, for example, we listed what we had learned that was valuable for our heads, for our hearts, and for our hands (meaning: things we could use practically, tangibly).

For me, this practice of intentional, nearly continuous learning was at least as rich as the individual insights we collected. The experience of learning actively, playfully, with a sense of curiosity and surprise, was part of what made the Camp feel so alive.

And it raised the question: what if our work were always (or at least more often) like that? And why isn’t it already? After all, Peter Senge first wrote about the “learning organization” over 20 years ago; since then, it’s been universally acknowledged as a critical factor in organizational success. But it’s still not the norm. So why not? And what would enable it to be?

To answer these questions, we first have to distinguish between training and learning. I’m not talking about the simple transfer of facts or the acquisition of basic skills. I’m talking about active participation in developing insights that weren’t previously available. The value and practices of training are well understood in the business world. But learning… not so much.

In my experience, if learning is recognized and embraced at all in business, it’s as a means to produce and sell more stuff. It’s one way to oil the machine. At first glance, this makes sense. But the problem is that this view stifles our interest in learning – there are more direct ways to sell stuff, after all. And it limits the learning experiences we create, blinding us to opportunities for powerful, integrated practices.

Here’s an example of what I mean. I remember when the first Chief Learning Officer was hired at the multi-national corporation where I worked in the 1990s. He was a brilliant, passionate, likeable guy. And he was totally ineffective. He quit out of frustration after only a few months. Despite verbal support from the top, the activities he proposed were seen as add-ons to the real task of producing and selling stuff. And the connection between the two was too indirect. From what I’ve seen, the situation hasn’t changed significantly since then in most organizations. And it’s a missed opportunity of huge proportions.

Instead, what if we looked at the role of learning completely differently? What if we viewed producing and selling stuff as a means to learning? What if the goal of our work is actually to play and learn together, and producing and selling stuff is simply the game and playground equipment at hand?

Integral philosopher Zak Stein has a similar thought:

Policy and rhetoric consider the function of the educational system as merely to supply our vast global economy with human capital; educating entrepreneurial global citizens or building skills for the global work force. But what if we turned this on its head? What if we understood the economy as merely an infrastructure enabling a vast educational system, with all our entrepreneurial efforts channeled toward the betterment of human understanding and experience?

It’s a radical idea – absurd, even, according to today’s business logic – until we consider that we and our organizations are not machines to be oiled, but dynamic living systems to be nurtured. And what makes a living system thrive is not more stuff. It’s not “busi-ness” and activity for its own sake. It’s connecting, sensing, responding and learning.

This is indeed the view of those at the very heart of the organizational learning movement. For the past twenty years, though, much of the learning organization conversation has focused on systems thinking – the idea that an organization is a complex system, rather than a simple mechanism. This helps us see that we must attend to the pattern of connections if we want to shift the parts or the whole. And that has been an important advancement. But with its origins in cybernetics, systems thinking generally leaves us with the view that an organization is still a machine – just a more complex one than we originally thought. As a result, we haven’t seen a meaningful shift in practice.

In recent years, however, we’ve begun to go further, recognizing that an organization is a living system, and therefore a learning system. With this change in perspective, we’re starting to challenge the very goals of business. And a widespread shift in practice won’t be far behind.

The point of all this isn’t to say that your organization’s practical mission – to produce and sell stuff – isn’t important; it’s to expand that mission and to put it in perspective. It’s to recognize that our organizations are living extensions of the people within them. They’re dynamic human communities. And it’s reasonable and important to expect them to serve a wide range of our human needs, including learning.

Generation Y already gets this. According to the stereotype, they’ll choose a job with rich learning opportunities over one that pays more money but offers little enrichment.

And both intuitively and empirically, we know that the more and faster our organizations can learn, the more innovative, adaptive and competitive they will be. So there’s little compromise involved in embracing the idea of a living, learning organization.

What will it take, then? And what will it look like?

Here’s what our Thrivability Camp experience suggests:

- Predictably, we will spend more time, more often, examining what we’ve learned.

- But we will also approach our work with a different attitude. Learning takes place even in the doing, as well as in times of paused reflection. When we go into the doing with an attitude of playful prototyping, it creates a very different experience – and a richer outcome.

- Learning is most engaging when it is clearly connected to an inspiring shared purpose.

- And it is most powerful when it is both individually and collectively generated. For example, at the Camp each participant was invited to contribute to the group’s learning, sharing practices and examples from their own experience. We also processed our learning both individually and as a group.

- This weaving of individual and collective learning requires an investment of time to build both trusting interpersonal relationships and a strong sense of coherence within the group.

- It is also supported by individual practices of mindfulness and personal responsibility. Collective learning is necessarily self-organizing and so requires each participant to take ownership of what they contribute, as well as what they take away.

- At the same time, while collective learning is self-organizing and emergent (you don’t really know what insights are going to emerge), it is most effective when supported by a skilful and adaptive host or facilitator – and preferably more than one.

These are some of the factors that make start-ups feel so alive – playful prototyping, trusting relationships, inspiring shared purpose, ongoing learning at multiple levels. And it’s when these factors fade away that organizations start to feel like lifeless machines – and so do we. But it doesn’t have to be this way. As we embrace the living systems view – and as we recognize that, by definition, thriving is learning – the role of the organizational leader becomes less engineer and mechanic and more host and gardener, ensuring that these fertile conditions continue to be present.

All of this is vitally important not only at the individual and organizational level. If learning were recognized as a primary goal of our economic activity, Stein contends that “the blossoming of the social imagination would follow.” The dire challenges we face as a species require nothing less.

[If you enjoyed this article, consider subscribing to receive future posts by email.]